A poem of mine, Thighbones, Clay, is up at Eunoia Review.

Another entry in the intermittently active Bookmarks series. This is actually a receipt not a bookmark, but I’ll allow it.

Sixty years ago today, one of the two men I was named after — my Opa Nicolaas — dropped dead suddenly as he was getting into a cab in ’s-Gravenhage, his arms laden with Sinterklaas presents.

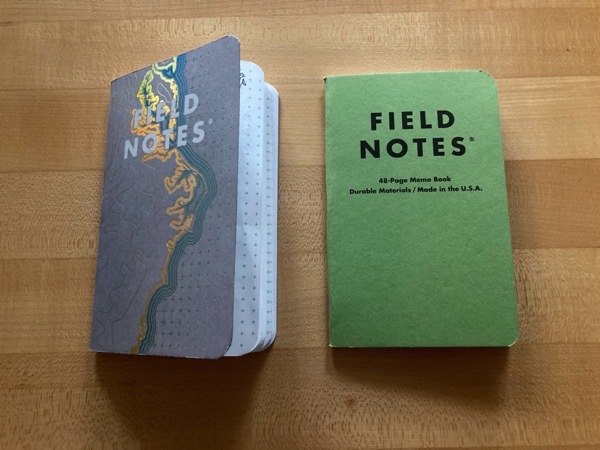

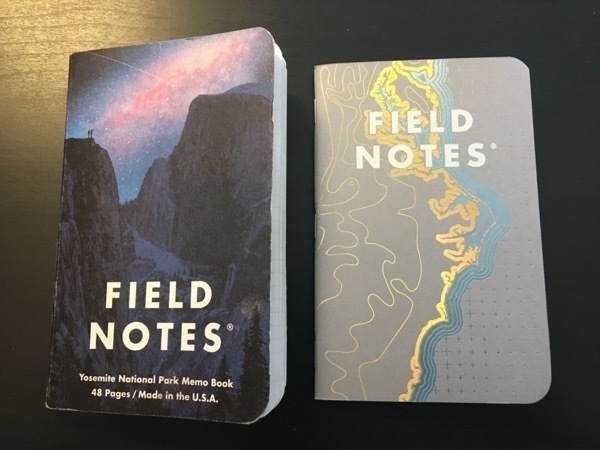

72: United States of Letterpress (Starshaped Press)

73: Nat’l Parks (Denali)

I’m appalled to discover I have a book-length manuscript of poetry written in 2020. How is this possible? I swear I spent the year hiding in bed or crushed in a chair staring blankly at the pages of one unread book or another. Frankly, I feel a little queasy that this shitshow year has been so productive for me.

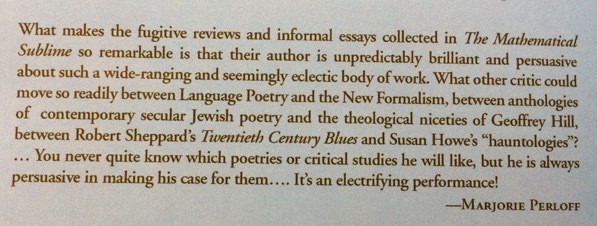

A late entry to the Bookmark project. I pulled a book off the shelf just now and stumbled on this:

Well, it’s 8:45 on a Sunday night. Time to drink too much wine, revise old poems until they’re indecipherable, and listen to this on repeat.

My (Small Press) Writing Day

#Are you looking through the bent-back tulips to see how the other half lives? Well, now you can satisfy your literary voyeurism without all that skulking under windows or peering furtively through the hedge!

How I Build Things

#Writer’s block is the unwillingness to crawl. — Eve L. Ewing

(1)

I wasn’t always an early riser, but at some point in the first year or so after college, I had a temp job that started at about six in the morning. For two months, in the darkest stretch of winter, I woke at four, stunned and blasted like an atomic atoll. I clung to my little kitchen table, stared blankly out at the silence. Then I drove through an empty city to a cold office behind an icy parking lot.

I soon moved onto my next job, which had very similar hours. And some semblance of a new routine began to coalesce. As the world slowly woke up around me. And I formed the habit of slowly waking up into writing by the window. I have remained an early riser ever since.

What I discovered almost immediately was that this early in the morning, the Artist is still sleepy and the Editor hasn’t even woken up, so no one is really thinking too hard about what’s being written down. Then, later on the day, when the Editor is in the Office and the Artist is ready to stare out the window with a glass of wine, the Editor can go over the pages, selecting, cutting, rearranging, maybe jotting down questions in the margins for the Artist to look at.

This sort of rhythm could have worked equally well, of course, had I stayed a night-owl: late nights for the Artist, the next morning for the Editor. This, in fact, was more or less what I’d already been doing. But that temp job helped me realize that there was something about the night-owl pattern that was not, in fact, working well for me anymore.

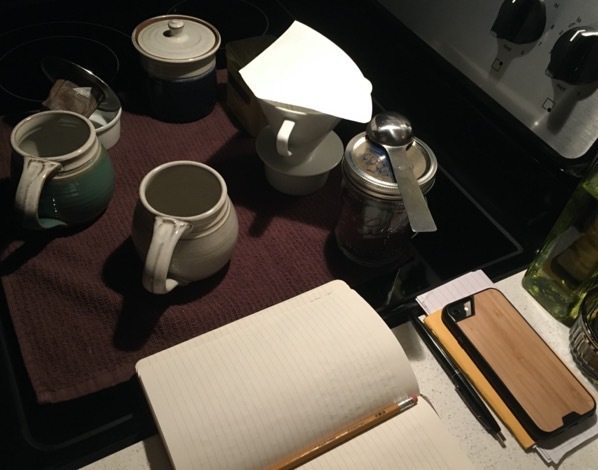

To this day, I keep a notebook open on the kitchen counter in the morning as I make my coffee. I call it my “Ongoing” notebook. I jot down sentence fragments, syllabic rhythms, snippets of nonsense. Sometimes only a few lines, sometimes a full page, sometimes — all too often — nothing. I fill about two or three of them each year.

With some variations, this has been my overall routine, even when it wasn’t. Something I’ve noticed about me: simply knowing I have a plan helps me get work done, even — or especially — if I don’t follow the plan.

(2)

But this year has been different.

Beginning in February, I stopped keeping an Ongoing notebook with me. I was just filling it with rants about the repugnant slug in the White House, or Covid. I’d stayed with it for a while, thinking that by letting those thoughts have their time, I could get them out of my head and I could move on with my morning. This had worked in the past. But now I found it actually amplified these thoughts, cementing them more firmly, which set the grim, desperate tone for the morning and for the day.

I decided I simply didn’t need to record these thoughts. It’s difficult for a writer to think that it’s okay not to write. But it is okay: let it flow past with the current. Watch it, but let it go.

Then, in March, I needed to prepare my home office to accommodate video conferencing when my day job switched to Distance Learning. As I shuffled things around, I discovered to my surprise that I had twenty-three Ongoing notebooks, going back to roughly 2011, which I had hardly been reviewing enough over the last few years. Instead, for most of this last decade, I was pushing on, filling more pages, filling more notebooks, with hardly a backward glance. How many poems were lying hidden in those years of messy first drafts? I decided to take some time to look at them again. I gathered them together – and, in the boring excitement that was March through May, I forgot about them.

In June, I noticed the stack in the corner, and I carried them to the kitchen table and finally got to work. Since late June, then, I have been slowly working my way through the Ongoings, an hour or so each weekend, two or three notebooks at a time.

Here’s what I’m doing.

1 — I skim each page with a red pen and post-it flags. If a passage, sentence, or a word catches my eye, I draw a quick red line down the margin, or box it, then flag the page.

2 — When I finish a notebook, I go back and cut the flagged pages out of the notebook and toss the excised sheets in a folder.

3 — After going through seven or ten notebooks, I quickly sort the accumulated loose sheets into three groups:

* “poem”

* “essay/blog”

* “???”

The key to these first three steps is quickly. I move fast and I don’t think too much. Thinking is for later. Am I going to miss some good stuff? Maybe. But what’s “good” anyway? I’m looking for interesting, for puzzling, for confounding. And if I overlook something, I’m not worried. It’ll be there the next time I pass through the notebooks. And my definition of “good” and my preoccupations will have shifted, so different things will catch my attention.

Okay, so now I have three stacks. This is what I do next — and, again, I try to move as quickly as possible:

4 — I go through each stack and sort them into smaller groups:

* beginnings and endings

* fragments in search of other fragments

* rough but whole

But what do I mean by “beginnings and endings”? And how do I know which fragments are seeking other fragments and which are just… fragments? Good questions. I don’t know, and I don’t really need to know. I’m basically chick-sexing here. It isn’t my job during the sorting to be able to defend why any fragment is going into one category rather than another. It doesn’t even matter if I’m wrong. The important thing is to put them somewhere.

And by putting the fragments into these broad, rough categories, I’m making the next stage just a little easier. That is, now I have fragments that are waiting either to be assembled, or expanded, or simply polished. This means I have a fairly good idea which activity I’ll be engaging in before I’ve even read a syllable of text.

Each of these — assembling, expanding, polishing — are, of course, very different activities and they involve different creative strategies. By matching the work with my energy level, I will be just a little less likely to burn out or feel overwhelmed as I begin my editing, or composing, or remixing.

This was a fairly easy process to develop, since it was a simplified, stripped down version of how I almost always build everything – songs, poems, essays, even email messages. I let fragments accrete then I allow coherence to develop through the accident of proximity. I listen for any odd or jarring leaps and I reshuffle things, either filling in those gaps or making the gaps wider.

The clean, chronological narrative of a final draft of writing is an illusion. We start with hunches and look for ways to explain them. Thoughts begin within webs of associations, and only later do we, with any luck, discover the strong supporting evidence that built them.

We start with meandering paths and dead ends, and only later do we present the final “short cut” that got us from there, to there, to there, to here. Whether you do all that wandering and orienteering “in your head” or on sheet after sheet of messy notebook pages, the work is unlikely to proceed in the orderly and logical progressions we present in our fastidious, crisp, spell-checked final drafts. Even logic is not nearly as logical as we think it is. There are wild, shocking leaps in even the simplest of syllogisms. We just craft them to seem like the leaps were inevitable. And who’s to say they weren’t? It all depends on where you were trying to leap to.

71: Autumn Trilogy (Elm)

72: United States of Letterpress (Starshaped Press)

A Day in the Life

Minneapolis, 05:30 CDT

How I begin every morning

tea for her

coffee

and the blank page

for me

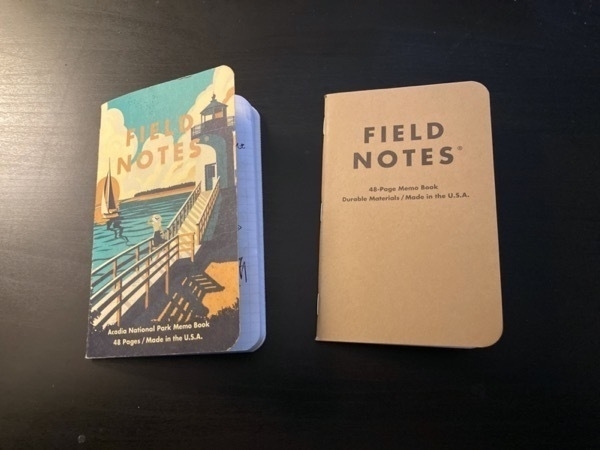

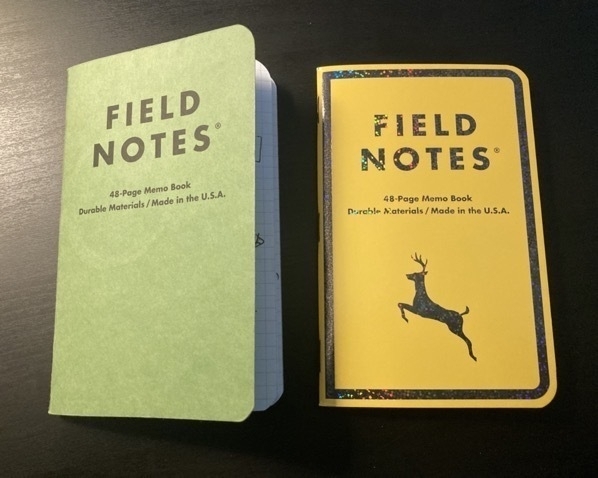

70: Kraft (lined)

71: Autumn Trilogy (Elm)

69: Nat’l Parks (Acadia)

70: Kraft (lined)

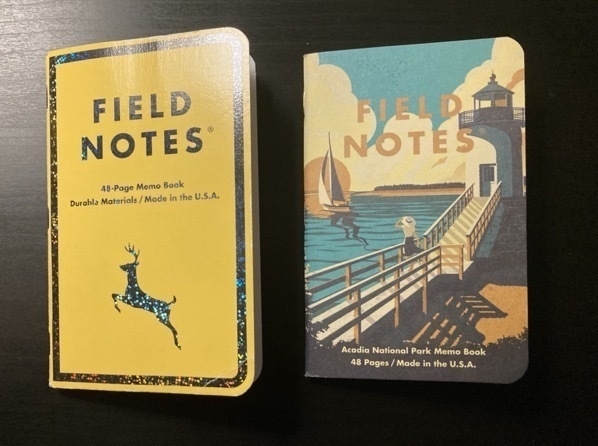

68: Mile Marker (Deer)

69: Nat’l Parks (Acadia)

The Acadia is yar.

67: Wednesday Green

68: Mile Marker (Deer)

Perloff’s Blurb

#

Marjorie Perloff’s blurb on the back cover of Mark Scroggins’ The Mathematical Sublime is an inadvertant description of exactly what bothers me about too much contemporary poetics and criticism. Why shouldn’t a critic be able to handle both langpo and formalism? Why does such eclecticism strike Perloff as so remarkably rare? Everyone outside Academia is exuberantly, unapologetically, and often instinctively eclectic.

I agree with her that Mark Scroggins is “unpredictably brilliant and persuasive.” I’m just annoyed because her blurb reminds me that everything she praises him for shouldn’t be so damn unusual. If you’re a cultural critic, you have one job: to range as widely and deeply as possible through human culture and send back reports of your remarkable discoveries. Perloff is praising the window frame when she should be admiring the view. And her blurb implies she doesn’t look out very many windows.

If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they don’t have to worry about answers.

—Thomas Pynchon, born on this day in 1937, and who’s been sporting a face mask for years:

66: Coastal (Chesapeake)

67: Wednesday Green

Six Zoom Meetings Before Lunch

#on self-care, timelessness, and boundaries

I watched a few episodes of The West Wing recently. I joked that I was playing a West Wing drinking game. I would drink whenever:

- Josh has his backpack over one shoulder

- any reference to a musical

- “Just saying”

- “Jackass”

- Walk and Talk

- Donna asks Josh to explain something

- someone repeats verbatim what someone else just said

And I would take a double drink for:

- any Latin phrase

- Mrs Bartlet’s terms of endearment

- Someone refers to their SAT score

- The Jackal!

The implication here was that I’d be drinking pretty much constantly – which was the point, because it was that kind of night. I could just as easily have said I was playing a Stare At The Wall drinking game. You drink whenever you stare at the wall. Double for blinking.

I knew it was likely, after my post appeared in the Micro.blog timeline, that people would say something about how it’s too painful to watch a show like The West Wing now. Of course it is. But then, everything – even self-care – can seem too painful now. So I figured: if joy is laced with pain anyway, I might as well take comfort anywhere I can. And some of that comfort comes from watching escapist TV.

Where I’m escaping to is, of course, jarringly different from the world as it is now. But this, too, has been oddly helpful. It has let me practice the transition back and forth between these two worlds, the comfort world and the Covid world. That moment of reëntry is, I think, what we actually find most painful: when we look away from the screen and see, out on the sidewalk, people walking by with face masks on. Oh, that, we think. I’d forgotten.

I’ve worked from home partly or completely for many of the last twenty-two years. One thing I learned early on was how important it is to set clear boundaries at the beginning and the end of the work day or else everything might start to blur together. So, in March, I thought this quarantine wouldn’t be too unfamiliar, or too challenging. I was wrong.

Working from home is, of course, vastly different from living in quarantine. The numbers on the clock almost never seem to line up with my sense of what time it is. If an event isn’t on the calendar, if a to-do isn’t pinging me with a repeating notification, it simply doesn’t happen. I keep hearing Ford Prefect saying, Time is an illusion, lunchtime doubly so. (I’ve been trying to write this blog post for nearly two weeks and I just haven’t been able to get my shit together to finish it.)

One reason for this is that many of the normal boundaries around different activities and emotional spaces have broken down or disappeared (for instance, commutes). I have found that I need to be far more conscious than usual of what sorts of routines and rituals demarcate different activities for me.

When I have good days, it’s at least partly because I’ve managed to maintain strong borders. And when I have better days, it’s at least partly because I’ve been able to cross back and forth over those borders somewhat smoothly, with as little stumbling as possible (by which I mean, a lot of stumbling but not as much as on other days…).

And by letting (or making) myself drift away into truly escapist activities like old beloved TV shows, I am slowly learning, and practicing, how to cope with the shock of returning, again and again, to this world.

April 2022: Some tangents that I trimmed from the early drafts of this post went on to become this essay.

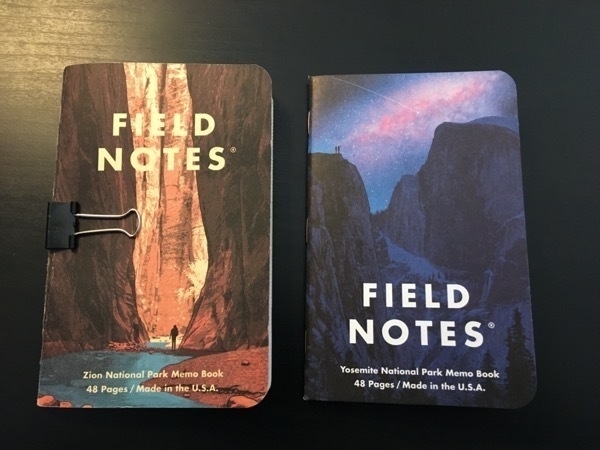

65: Nat’l Parks (Yosemite)

66: Coastal (Chesapeake)

My Plan for National Poetry Month

#Now that shoures soote the droghte of March hath perced to the roote, it’s time once again to breed lilacs out of the dead land, mix memory and desire, and generally stir dull roots with spring rain.

Yes, that’s right: it’s NaPoWriMo.

This year I’m returning to an old practice I did in 2004, ’05, and ’06. Each day this month, I’m doing an exercise from Rita Dove called the 10-Minute Spill, which I found in the delightful Practice of Poetry.

Here’s how it goes: With ten minutes on the clock, write a ten-line poem using five words from a predetermined list, and an adage or idiomatic phrase (e.g. a stitch in time— don’t count your chickens— that sort of thing).

And that’s it. Don’t try anything fancy: no rhymes or meters of any sort. Just spend ten minutes figuring out how to pepper the words and the folksy saying over the course of ten lines. How long is each line? Doesn’t matter! Is it even a poem? Who cares!

For my list of words, I’m using the Swadesh List. There are a hundred words, and so I roll 2d10 five times. And for my “adage,” I’m throwing the I Ching and choosing something meaty from the trigrams' names and the resulting hexagram’s image and judgment.

I’ve done three “poems” so far and they may be kinda crappy but none of them are about Covid-fucking-19, so I’m calling it a win.

A reminder of one of the many, many reasons why I left Oregon. From the New York Times, 21 Feb 2020:

In Portland, a city often portrayed in popular culture as a progressive paradise, the killing of the men provoked outrage, along with reassurances that the city would not tolerate hate. But it also set off a new round of questions about whether Oregon had fully shed the legacy of its founding as a racially pure Cascadia that white supremacists still fantasize about.

Oregon was admitted to the Union in 1859 with a constitution that, uniquely, forbade black people from living, working, or owning property in the state; the provision was not repealed until 1926. In the 1920s, the state legislature barred Japanese immigrants from owning or leasing land. By the 1970s, extremist groups like the Aryan Nations had found fertile ground for their beliefs.

64: Nat’l Parks (Zion)

65: Nat’l Parks (Yosemite)

Jim Lehrer’s Rules of Journalism

- » Do nothing I cannot defend.

- Do not distort, lie, slant, or hype.

- Do not falsify facts or make up quotes.

- » Cover, write, and present every story with the care I would want if the story were about me.

- » Assume there is at least one other side or version to every story.

- » Assume the viewer is as smart and caring and good a person as I am.

- » Assume the same about all people on whom I report.

- Assume everyone is innocent until proven guilty.

- » Assume personal lives are a private matter until a legitimate turn in the story mandates otherwise.

- » Carefully separate opinion and analysis from straight news stories and clearly label them as such.

- » Do not use anonymous sources or blind quotes except on rare and monumental occasions. No one should ever be allowed to attack another anonymously.

- Do not broadcast profanity or the end result of violence unless it is an integral and necessary part of the story and/or crucial to understanding the story.

- Acknowledge that objectivity may be impossible but fairness never is.

- Journalists who are reckless with facts and reputations should be disciplined by their employers.

- My viewers have a right to know what principles guide my work and the process I use in their practice.

- » I am not in the entertainment business.

(via Kottke, who notes, “In his 2006 Harvard commencement address, Lehrer reduced that list to an essential nine items, marked with » above.”)

Credulous, Cowardly, and Vicious

David Bentley Hart (via):

The 2016 U.S. election proved that, even in a long-established democratic republic, just about anyone or anything, no matter how preposterously foul, can achieve political power if enough citizens are sufficiently credulous, cowardly, and vicious.